Shareholder proposals published on a company’s proxy statement, to be voted upon by all stock owners at the annual meeting, are subject to certain rules.

One rule is that the first shareholder proposal on a particular topic or issue — if it fulfills all the other required criteria under the rules — gets to be the proposal that will be considered at the meeting. All subsequent proposal submissions on the topic are excluded from the proxy statement for that year.

There are many types of proposals, and the process has been dominated by the political left for decades. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) priorities are the focus of most shareholder proposals.

The “G” component of ESG presents opportunities for support by an ideologically broader range of shareholders than “E” or “S,” because governance is about the rules and bylaws a company chooses to manage itself. National Legal and Policy Center the past two years has sponsored several proposals that fit the “G” category, including requests for greater transparency about charitable contributions and lobbying expenditures. Another proposal we have introduced extensively is one that requires a board of directors to implement an “independent chair” policy, which means the Chairman of the board and the CEO cannot be the same person.

Recently NLPC has learned that some left-leaning activists who specialize in governance proposals are extremely unhappy that we are honing in on their territory. We find it quite comical.

John Chevedden

The activists are part of a small group led by longtime activist John Chevedden, who strategize together about which proposals to present at each company. The other proponents on his team are James McRitchie, Myra Young and Kenneth Steiner. Independent chair proposals are one of their frequent submissions, and presumably they’ve seen them easily move through to proxy statements without obstruction, because few if any others introduced them. NLPC has changed that.

First, a bit more about the rules. When a company receives a proposal from a shareholder, it does everything in its power to try to keep the proposal from appearing on the proxy statement, so the board of directors sic their legal team on it. If the lawyers can find a technicality or another rules basis to exclude it from the proxy, they will raise the objection(s) on behalf of the company. If the proponent won’t or cannot “fix” the alleged violative issues, but still demands that the proposal appear on the proxy, then the company appeals to the referees at the Securities and Exchange Commission, requesting to allow the company to omit the proposal without penalty from the agency.

That’s where Mr. Chevedden enters our story, pertaining to our independent chair proposal for Bank of America Corporation earlier this year. Mr. Chevedden’s colleague, Mr. Steiner, submitted an independent chair proposal for the company, but we at NLPC submitted ours first. So Bank of America asked the SEC’s referees to allow the company to exclude Mr. Steiner’s proposal from its proxy because it planned to include NLPC’s version, because we were first.

When a company informs the SEC that it plans to exclude a proposal and the agency must decide whether to allow it, it opens a docket in which its lawyers present the reasons, and the proponent often attempts to rebut the lawyers’ rationale for exclusion. In the case of the Chevedden/Steiner proposal for Bank of America, the pair’s arguments against our proposal, and in favor of theirs, had more to do with their opinion about NLPC rather than the nature of our independent chair proposal itself. You can see the docket of back-and-forth correspondence between the parties here on the SEC website.

To pursue its exclusion permission from the SEC, Bank of America enlisted outside law firm Gibson Dunn to make its case. It is common for corporations to hire outside legal specialists to handle this for them. So the docket began with the law firm’s pleadings as to why the Steiner proposal should be omitted from the proxy statement. Then the fun began.

Gibson Dunn attached various exhibits to its pleading to the SEC, which included NLPC’s proposal (Exhibit B) to show that ours arrived at Bank of America first. Following that are responses from Mr. Chevedden.

He began by confusing NLPC with our friends with a similar name, the National Center for Public Policy Research (NCPPR), which also is on the right-leaning side as shareholder activists.

Another SEC rule requires that proponents provide companies with letters from their stock brokers to prove that they actually own enough shares to qualify to sponsor a proposal. We had sent our letter to Bank of America, but Mr. Chevedden errantly told the SEC staff that NLPC had been “having a big problem with broker letters.” This was not the case for us, but it was for NCPPR (which Mr. Chevedden confused us with), whose broker earlier this year served them extremely poorly.

But Mr. Chevedden continued with his mistaken assumption in his attempt to get his proposal accepted instead of NLPC’s: “I do not believe that management can overlook a defective broker letter and thereby include the proposal of Proponent A in its annual meeting proxy in preference to Proponent B, who has a valid broker letter.” He then demanded that Bank of America to send NLPC’s broker letter to the SEC, to prove our legitimacy.

Having stewed on it further, five days later Mr. Chevedden repeated his demand for NLPC’s broker letter, speculating that if the company wanted to defeat a proposal in concept, it could let an inferior version (like NLPC’s) to appear on the proxy statement, to “defeat a qualified shareholder” (like Chevedden/Steiner!).

Gibson Dunn, Bank of America’s legal counsel, then supplied the SEC with a copy of NLPC’s broker letter as proof that we had delivered it to the company (see Exhibit S-3). Having failed to disqualify NLPC’s proposal based on the broker letter requirement, Mr. Chevedden then switched to calling our shareholder activity into question based on ideological grounds, telling the SEC, “Perhaps Bank of America is happy with the National Legal and Policy Center sponsorship…the organization has a number of controversial political positions that will drive shareholder (sic) to vote against a worthy…proposal topic.”

To highlight his objection to our sponsorship, Mr. Chevedden attached as documentation our filing at the SEC in support of an independent chair proposal we sponsored early this year for Visa, Inc. Mr. Chevedden pointed out our criticisms of Visa’s support for the violent and corrupt Black Lives Matter movement and for anti-2nd Amendment initiatives as examples.

That wasn’t all. In one final missive to the SEC, Mr. Chevedden again argued against our version of the Bank of America independent chair proposal because NLPC “boldly injects divisive political views into the issue of improved corporate governance and thus has the potential to alienate about 50% of shareholders.” His frustration was palpable.

“Proposals on established [governance] improvement topics by the National Legal and Policy Center could be called poaching proposals because they steal the topic from a proponent that does not dump divisive political views into the discussion,” Mr. Chevedden wrote.

While Mr. Chevedden and his team attempt to have shareholders believe that they are apolitical, his group sponsors their own environmental and social (i.e., political) proposals as well, include ones on “climate lobbying” — asking Boeing, for example, to disclose how its expenditures align with Paris Agreement goals and “efforts to limit temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius.”

Chevedden and his allies also work with the radical leftist shareholder activists at As You Sow on ESG proposals, and five years ago his group betrayed their claim to an apolitical approach by stating his team would expand beyond governance proposals because “we recognize democracy must be won on many fronts.”

Which further illustrates the problem the Left has. They believe theirs are the only objective and reasonable views that should be considered, and that all who disagree (like NLPC) must be muted and shut out of the political process — or likewise, out of the shareholder activism process.

As Mr. Chevedden and his allies infer, they have owned the corporate shareholder battle “front” — and the SEC should let them keep it that way.

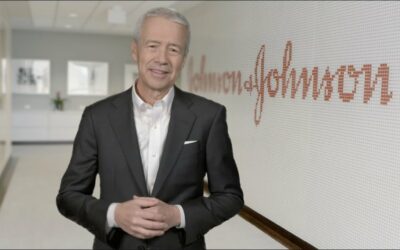

(Pictured above: Bank of America Chairman/CEO Brian Moynihan was heavily criticized by NLPC when it presented its independent chair proposal at the company’s annual meeting in April)