One of the more enduring principles of labor law in America is that workers who are unhappy with their union representation have the right of exit. The current National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) seems determined to narrow if not eliminate this right. On April 21, the board, by 3-1, ruled in Mountaire Farms Inc. that all ballots cast by about 800 Delaware poultry workers as part of an effort to decertify a local affiliate of the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) must be destroyed. A number of workers at the plant had challenged the basis for applying the “contract bar,” which prevents workers from holding a vote until at least three years into the contract period. After the ruling, National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation President Mark Mix accused the board of using labor law as “a protection racket for incumbent union officials.”

Workers often develop buyer’s remorse after going all-in with a union. Whether their dissatisfaction concerns dues assessments, financial integrity, handling of worker grievances, or some other issue of union representation, employees may seek to vote to decertify their union as a bargaining agent. In practice, going this route is easier said than done, thanks to a decades-long NLRB doctrine known as the “contract bar.” Here, workers cannot hold a decertification vote until three years after the current collective bargaining agreement takes effect. Dissenting workers are also limited in that the decertification action only can be filed during a 30-day “window” normally lasting between 90 and 60 days prior to contract expiration. The doctrine is customary. That is, it is not specified in the National Labor Relations Act.

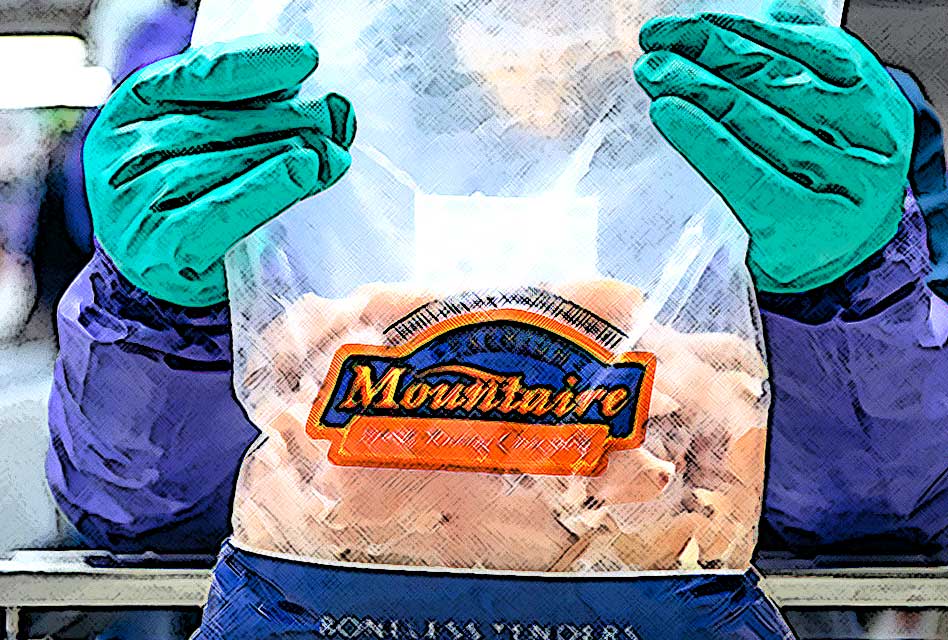

Unfortunately, the starting point of the “window” isn’t necessarily clear. That was the case for employees of Mountaire Farms, a Millsboro, Delaware-based poultry processing firm with operations in Delaware, Maryland, and three other states. Workers at the company’s Selbyville, Del. plant were dissatisfied with their representation from United Food and Commercial Workers Local 27. Seeking release from their collective bargaining agreement, several employees at the facility last year circulated a petition among their peers, eventually collecting enough signatures to trigger an NLRB-supervised decertification vote. On June 23, the board regional office granted the request. On July 7, the NLRB invited the submission of amicus briefs on the issue of whether the contract bar in this particular case applied. Over 15 entities responded. Clearly, this case had implications beyond the poultry processing industry. The employees proceeded to hold mail-in balloting that lasted until July 14.

Section 8(a)(3) of the National Labor Relations Act requires that following the establishment of a collective bargaining agreement, a nonmember incumbent employee or a new hire must become a union member, or pay partial dues (“agency fees”) to the union in lieu of joining, within 30 days. These union “security clauses,” as they are known, require a private-sector employer to fire any employee who refuses to pay. Apropos of this case, the 30-day period may begin either on the date the agreement goes into effect or the date a worker is hired, whichever is later. Any security clause tied to the date of the agreement must be worded to ensure that employees are granted this grace period. An individual state may make this issue moot, of course, if it has a Right to Work law. At present, 27 states have such laws on the books. Delaware is not one of them. As such, Mountaire workers at the Selbyville plant could not opt-out of having dues deducted from their paychecks.

Plant management had entered a collective bargaining agreement with UFCW Local 27 on February 8, 2019. The contract covered the period December 22, 2018-December 21, 2023. A number of workers did not like the agreement from the start, believing that the union had rigged the wording of the security clause. The clause, they argued, gave workers who had begun their employment after the agreement a smaller window. These dissenters were irritated to the point of wanting to their union representation and associated dues assessments. The union, predictably, did not accept this request. At that point, the workers, led by one Oscar Cruz Sosa and aided by the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation, went to the National Labor Relations Board regional office, requesting approval to hold a decertification vote.

The dissenters would win that round. NLRB Regional Director Sean Marshall concluded that the security clause “effectively groups employees into two categories: the first is employees who are members of the Union in good standing at the time of the Agreement’s execution, and the second [is] those employees that are not Union members at the time the Agreement was executed.” In other words, the union had made it much more difficult for people hired after the finalizing of the agreement to receive a 30-day window of refusal. Buoyed by the ruling, union members, with the support of their employer, circulated a decertification petition, eventually obtaining signatures from the required 30 percent minimum of affected workers. A decertification vote was on.

United Food and Commercial Workers Local 27, meanwhile, had filed an appeal with the NLRB in Washington, D.C. And last Wednesday, the normally five-member board voted 3-1 that the three-year contract bar was applicable. The majority, consisting of Lauren McFerran, Marvin Kaplan, and William Emanuel (the latter two, curiously, Trump appointees), concluded that the union security clause in question did not deny veto rights to workers hired after the establishment of the collective bargaining agreement. “In sum,” the majority concluded, “we find that the union security clause is, at most, ambiguous with regard to its retroactive application to incumbent nonmember employees. As such, it is neither ‘incapable of a lawful interpretation’ nor ‘clearly unlawful on its face.’” The ruling added that the proper forum for determining whether or not a union security clause is unlawful is through an unfair labor practices suit. It also canceled the vote count and ordered all ballots destroyed.

The board’s lone dissenter, John Ring, took a much different view. He stated that the clause in question “is not carefully worded” insofar as it applies to people hired after the contract went into effect, and “obviously deprives those employees the requisite statutory grace period.” UFCW Local 27, he concluded, deliberately attempted to create ambiguity where there previously had been none. In so doing, it undermined the main purpose of collective bargaining, which is to keep labor peace. “The premise of the Board’s contract-bar doctrine is that the statutory right of employees to change their bargaining representative may properly be deferred for a limited period of time when a collective bargaining agreement is in force, in the interest of promoting industrial peace and stability in labor relations,” Ring concluded. “Under longstanding precedent, however, a contract containing an unlawful union-security provision cannot bar an election because such a contract ‘does not establish the type of industrial peace the [National Labor Relations] Act was designed to foster.’”

Mountaire Farms is a wrong-headed decision, but at least it has the unintended virtue of being narrowly focused. The larger issue, not decided here, is the constitutionality of the three-year contract bar itself. There is no intrinsic reason why a representative union should enjoy ‘hold harmless’ immunity for any length of time. If a sizable number of workers are dissatisfied with their union, they should have the right to vote that union out regardless of when they voted it in. The case against the contract bar rests on the same grounds as the case against forced dues payments generally. In other words, this is a Right to Work issue with implications for freedom of speech. Hopefully, a court of law will resolve the issue in favor of individual worker liberty.